|

|

Review of No Place Like Nome: |

|||

Review by Steve Giordano, photos as attributed |

|||

In No Place Like Nome: The Bering Strait Seen Through Its Most Storied City, Michael Engelhard crafts a compelling and nuanced portrait of a place that is often romanticized in popular culture, yet rarely understood. Far from a simple travelogue or a dry historical account, Engelhard's work is an insightful blend of cultural analysis, environmental observation, and personal memoir that reveals Nome as a microcosm of the larger Bering Strait region. It's a journey into a world where a man can strike gold one day and the next realize he probably should have just brought a warmer coat.

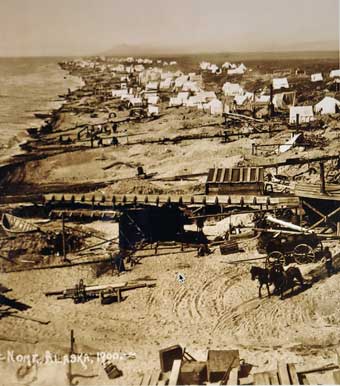

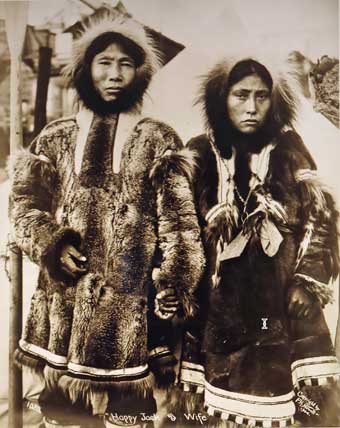

DISMANTLING A MYTH Engelhard's narrative begins by dismantling the myths surrounding the city, immediately confronting the image of Nome as a dusty, wild-west outpost of the gold rush. Instead, he presents a city with a rich, if tumultuous, history. He skillfully navigates the often-painful legacy of the gold rush era, detailing how the arrival of tens of thousands of prospectors in the early 20th century violently disrupted the life of the Iñupiat, who had inhabited the land for thousands of years. The book explores this historical trauma not as a distant event, but as a living part of the city's identity, influencing everything from land ownership to social dynamics. Engelhard's deep respect for the indigenous culture is evident throughout, and his interviews with local residents, both Iñupiat and descendants of settlers, provide a crucial, human-centered perspective on these historical events.

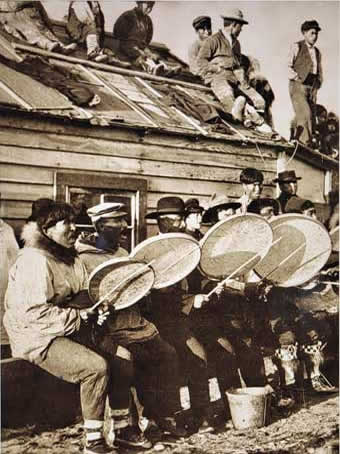

WHERE CULTURES COLLIDE Beyond its historical foundation, the book excels in its exploration of Nome's contemporary cultural and environmental landscape. Engelhard delves into the unique blend of cultures that defines the city today—a community where subsistence hunting and fishing coexist with the demands of a modern, cash-based economy. For example, Engelhard says, "To this day, Iñupiaq whalers sometimes repurpose a paddle as a simple but effective kind of sonar. With the blade in the ocean and the grip pressed against the echo chamber of their skull, they detect game moving underwater, through the wood’s vibration. They can distinguish bowheads from bearded seals—a question of volume—as if they were reading tracks in the snow."

A THOUGHTFUL EYE What makes Engelhard’s book particularly effective is his accessible and engaging writing style. He weaves his own experiences and observations—from walking the windswept streets to joining a group of birdwatchers—into the larger narrative, making the reader feel as if they are discovering the city alongside him. His voice is that of a thoughtful and empathetic observer, never preachy or judgmental, even when faced with a mosquito swarm so thick you could swear it had its own zip code. This personal touch infuses the book with a sense of genuine curiosity and wonder. Engelhard’s ability to find the profound in the ordinary—whether in the resilience of a community or the quiet beauty of the tundra—is the book's greatest strength. I particularly enjoyed the depth of his appreciation for how bicycles became a mode of overland and downriver transportation. An indigenous observer chortled, " White man, he sit down, walk like hell!"

No Place Like Nome reminds us that the Bering Strait isn't a distant, frozen frontier, but a vibrant and critical part of the world, full of stories that deserve to be told, and heeded. ABOUT THE BOOK'S AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE REVIEWER:

|