|

|

FOLLOW THE MUSIC — TO GERMANY |

|||

Story and photographs by Brad Hathaway |

Some of our best travel adventures have been trips to hear great music in concert halls, opera houses and musical theaters from Stockholm to Tokyo and Sydney to, of course, the West End of London, and New York’s Broadway. That made it somewhat less astonishing that, when I happened to mention to my wife that a new symphony by composer, Frank Wildhorn, would have a world premiere in Germany in about a week, she replied “Well, I haven’t got your birthday present yet so you should go!” When I said I couldn’t go without her she said “Then we should go!” So we went! You see, Wildhorn has long been a favorite composer of musical theater with six shows on Broadway (Jekyll & Hyde, The Scarlet Pimpernel, The Civil War, Dracula, Wonderland, Bonnie & Clyde) as well as musicals that have premiered and been hits in such places as Seoul, Tokyo, Vienna and Prague. Indeed, in 2008, in a similar gesture of love and support, my wife sent me to the Czech Republic to catch the premiere of Wildhorn’s musical of Carmen. It turned out that, as far as I know, I was the only American journalist covering the premiere of that musical.

That 2008 jaunt required a trip of only 4,279 miles since we then lived on the east coast of the US. Now, from California, attending the opening of Wildhorn’s second symphony at The Odessa Symphony, required a trip of 5,655 miles. We booked ourselves on a Condor Airlines flight to Frankfurt, then an Intercity train to where the concert would be held: Ulm, just 50 miles north of Germany’s border with Switzerland. While Wildhorn’s symphony provided a spectacular finale to our trip — more on that later — let's first look at this sumptuous southern German city of nearly 130,000. Checking into the strangely named Me and All Hotel, we began to explore. We found many modern buildings such as the modern art gallery called the Kunsthalle Weishaupt, the pyramidical glass City Library, and a multi-screen Cineplex.

But we soon found that there were sights dating back centuries. It seems that Ulm was founded on the banks of the Danube River in the year 850. Very little remains from that time, but much dates back quite a while. The Metzgerturm Tower, built in the fifteenth century, was once part of the city walls with a city gate in its base. Look carefully at the photo and you might notice that the tower leans slightly to the right — “The Leaning Tower of Ulm”?

Not far from the tower we found the Rathaus which has served as the town hall since the 15th century. High up its main wall you see an “astronomical clock” showing the position of the sun and the moon relative to the signs of the zodiac — but it takes an expert to actually read it properly.

There are half-timbered buildings throughout the older sections of town as well.

Whether you are looking at modern buildings or old ones, from most areas of the main city, one object dominates the skyline — the spire of the cathedral or Münster which, at 530 feet, is right now the tallest church spire in the world. That record will fall, however, later this year or next when the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona completes its Tower of Jesus Christ which will top out about 30 feet taller.

The city began construction of the Münster in 1377 when Ulm was one of the great centers of trade of the time. But, after a century and a half of construction, progress was paused due to an economic downturn. When they returned to construction centuries later, they had to lower their expectations. But they completed the tower to its originally intended height, while the church itself it is not as large as you might expect of a house of worship sporting the tallest spire in the world. But, as viewed from the huge open plaza, the Münsterplatz, it is an astonishing sight, especially in the glow of an evening’s dusk.

Entering the Münster itself, one finds it grand, indeed.

After our visit to the Münster, we spent some time watching the crew setting up the temporary stage in the Münsterplatz for the coming concert — hard to imagine a full symphony orchestra fitting on that stage, but it turned out just fine.

Another area that harkens back to a time long ago, when fishing along the Danube was a major economic activity, is the Fisherman’s Village, or fischerviertel. It spans multiple arms of the river Blau as it runs into the Danube. While it served fishermen, it also served tanners who found the fast flow of the water ideal not only for the power of the water wheels but useful in carrying away the chemical waste of their processes. Now, it is a wonderful tourist destination for scenic strolls and meals in fine restaurants by the waters edge.

Ulm seems to take great pride in the fact that perhaps the greatest mind of the 19th and 20th centuries was born here in 1879. Albert Einstein was born in an apartment building which was destroyed in the bombings of World War II. But his family moved to Munich when he was one year old. The location of the apartment building is marked today by a metal outline embedded in the pavement of the Einsteinplatz between a fountain where children play in the water and next to an abstract monument to his memory.

His memory is also acknowledged with a strange bronze fountain set before what was the Imperial Armory before the French took it during the Napoleonic wars. Conceived by sculptor Jürgen Goertz in 1984, it appears to be a rocket supposedly symbolizing technology with a large snail shell symbolizing nature out of which there appears the head of Einstein sticking his tongue out! I’m at a loss to explain it any further than that.

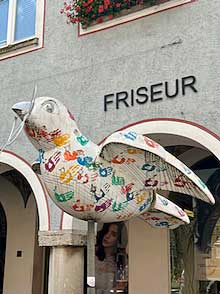

Ulm also holds on to a legend involving birds. Supposedly, workers constructing the Münster were having difficulty figuring out how to get a beam through the door when they noticed a sparrow carrying a straw in its beak turn its head to take it through a tight space lengthwise rather than crosswise. While it seems hard to believe that the construction workers of any time weren’t smart enough to know to take a beam through an opening that way, the legend has Ulmsters placing bird sculptures all around the town as advertisements of businesses or in park settings.

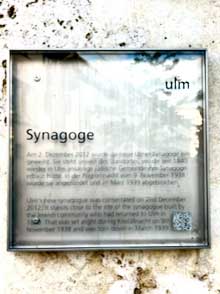

The history of Ulm includes the horrors of the Nazi period and the destruction of World War II, and Ulm doesn’t try to hide the unpleasant facts of its past. Before the new synagogue is a plaque pointing out that it is on the site of the old synagogue that was burnt down on Kristallnacht, 1938’s nationwide rampage against the Jewish population.

In front of the Regional Court Building is a memorial to the 1,155 people involuntarily sterilized and 183 murdered as “unworthy of life” under the Third Reich’s euthanasia statute. The location of the stainless steel memorial is particularly notable as it sits in front of the building in which the euthanasia statute was administered.

The city has done a fabulous job, however, of restoring and modernizing the central city areas all but obliterated by the bombing raids of World War II. The statistics are astonishing: of the 12,756 buildings that stood in the central city before the raids, all but 1,763 were destroyed. That is a total of over 85%! Still, the tower of the Münster survived — probably because such a prominent structure was of use to the bombardiers of the British and American forces as a landmark guiding their bomb runs to concentrate on targets such as the rail yard and factories. Today, what you see there is a thriving city with both old and new sights on plazas, along streets, rivers and canals.

While we had travelled to Ulm for the premiere of Frank Wildhorn’s symphony, we also took advantage of the fact that the venerable Theater Ulm was presenting a summer production of the musical Saturday Night Fever in an outdoor space. Theater Ulm is the oldest municipal theater in Germany, dating back to 1641. The musical played out in the central courtyard of the Wilhelmsburg, a nineteenth century fortress.

The packed audience seemed to thoroughly enjoy it. We had seen this musical in English a number of times in the US. Here in Germany, to see it performed in a translation into German, the story was still easy to follow and the characters easy to understand. The songs of the Bee Gees were sung in English, while the dialogue was translated into German by Anja Hauptman. The cast, while a bit mixed, had some strong performances in the leading roles. Most notable was Sascha Luder in the role made famous in the movie by John Travolta. Luder also shared choreography duties with Gaëtan Chailly. The overall look of the show by Petra Mollérus — the ausstattung which combines set, costume and properties design in a single person — was bright and colorful. A strong band with some players from Ulm’s symphony orchestra delivered the Bee Gees’ sound with enthusiastic energy.

Our brief stay in Ulm came to a climax when thousands gathered in the Münsterplatz before a temporary stage for the concert that had inspired our trip. Inside the fence were 2,500 chairs and it looked as if there wasn’t an empty seat in the area. How many others heard the concert I don’t know, but there was a crowd outside the fenced off area filling the rest of the space in the huge Münsterplatz.

One of Europe’s finest classical orchestras, the Wiener Symphoniker of Vienna, Austria, was here to perform music by Frank Wildhorn. That music features soaring melodies, extremely wide dynamic ranges from a hushed quiet to blasts of sound and rhythmic variety that maintains the audience’s interest over extended periods.

Wildhorn’s emergence as a composer of classical symphonic music can trace its origin to a challenge from one of his long-time theatrical producers, Walter Feucht, who is a resident of Ulm. He suggested that Wildhorn should compose a piece about the Danube River. When Wildhorn said he could do a song about the river, Feucht said it should be a symphony, not just a song. Shortly after that, the COVID pandemic locked everyone down and Wildhorn decided to use the shutdown time to explore just what he could do in a symphonic style. Working with his frequent orchestrator, Kim Scharnberg, he composed an amazingly virtuosic first symphony titled the Danube Symphony. It received its world premiere in 2023 by this same orchestra in the historic Golden Hall of Vienna’s Musicverein where symphonies by Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler had premiered.

The day before the concert, after rehearsals with the orchestra, I sat down with Wildhorn and Feucht to talk about this new symphony. Wildhorn spoke of the stories his mother had told him of the city where she was born — Odessa on the Black Sea, which was then part of Russia. Then he learned that Feucht’s father had also come from Odessa and, in fact, after the war had walked nearly a thousand miles from there into Germany, settling in Ulm. As they exchanged these tales a new, expansive, symphony emerged.

Before the concert began, Wildhorn and Feucht were interviewed on stage, sharing with the audience the story of how, after the success of the Danube Symphony, Feucht and Wildhorn found inspiration in the stories of their parents. Now, that orchestra was here to present the world premiere of Wildhorn’s Odessa Symphony.

This night’s concert began with two suites of music from Wildhorn shows which had premiered at the Theater St. Gallen in St. Gallen, Switzerland just 50 miles south of Ulm. Both musicals had been orchestrated by Koen Schoots who conducted this concert as he had the premiere of Wildhorn’s first symphony.

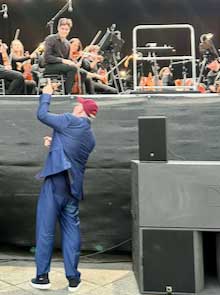

After the two suites, a well-timed rain shower led to a lengthy rain-delay that felt like a regular intermission. Then, the audience returned for the main event. The symphony opens quietly with a lovely violin introducing a gypsy-tinged melody which is played by different instrumental combinations throughout the first movement and will return later. After the full orchestra repeats that melody, about three and a half minutes in, a new and thunderous rhythmic blast caught the audience by surprise and an appreciative gasp could be heard throughout the Münsterplatz. Throughout the evening, it was clear that the musicians in the orchestra were enjoying playing the music as much as the audience seemed to enjoy hearing it. Wildhorn also was clearly overjoyed hearing his music so well played. This can’t be surprising given that the sound of a full symphony orchestra is strikingly different than that of a musical theater pit orchestra no matter how good its players might be. Probably the largest orchestra he enjoyed on Broadway was the 23 musician pit band for The Scarlet Pimpernel. This night there were 83 superb musicians on stage. At one point between sets Wildhorn was schmoozing with the musicians.

The Odessa is a seven-movement symphony; one feature of Wildhorn’s writing is that each movement builds to a distinct climax putting an emphatic ending to the movement. As a result, the concert included something one doesn’t often hear at classical concerts — the audience bursting into applause after each movement. Unfortunately, a different type of thunder greeted the end of the sixth and next-to-last movement this night. This thunder was accompanied by sheets of rain and flashes of lightning causing the performance to be prematurely ended. So, it remains to be seen where the seventh movement of Wildhorn’s Odessa Symphony will have its world premiere — maybe I’ll get to travel to catch that as well.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|