|

|

TRANSFORMING THE YUCATÁN: ARRIVAL OF THE TREN MAYA |

|||

Story and photos by Vicki Hoefling Andersen |

|||

I am once again slightly misplaced as to my whereabouts in the jungle. Some might say “lost” but I know if I follow one of the paths fading into the vegetation, I’ll eventually end up back near humankind. In the meantime I’m enjoying exploring an area I last visited over 17 years ago: the Río Bec region in Mexico’s southern Yucatán. I’m also here to get an idea of the massive changes transforming the entire Yucatán Peninsula, which I’d read about but had never imagined the enormity of the project that was underway. Definitely a case of Got-To-See-It-To-Believe-It! I’ve persuaded two fellow adventurers to join me on this trip: long-time friend and guide Alfonso Muralles from Guatemala City who owns and operates Four Directions travel company, and Kiyoko McDonald, author of the Japanese guidebook Travel the World of the Maya, Guatemala. For more than two decades we’ve explored dozens and dozens (and dozens) of ancient Maya cities throughout Mesoamerica. “Yucatán” is both a state in Mexico and a region; the Peninsula itself extends into northern Guatemala and Belize. Formed as a seafloor more than 65 million years ago, the area now shows that receding water levels during the ice ages have slowly revealed a low-lying, mostly flat terrain of porous limestone with few surface rivers or lakes.

It is famous for its cenotes, sinkholes in the limestone revealing subterranean rivers which provided drinking water for early inhabitants and are now bucket-list experiences for qualified cave divers. Honeycombed with underground grottos, these were sacred places for the ancient Maya, who left a wealth of artifacts for archaeologists.

Recent discoveries suggest that the first humans arrived in the Yucatán more than 26,000 years ago. In the north they found scrub vegetation and meager, nutrient-deficient soil. But in the south is the Maya Forest, second largest tropical rainforest in the Americas after the Amazon, and its cornucopia of flora and fauna. It’s no wonder people flourished, establishing sophisticated cities while the Roman Empire still had much of Europe under its thumb. Since there are no natural knolls in much of the Yucatán other than the Puuc Hills in the western portion (think 300-foot-tall wrinkles in the terrain), if you see a large mound it is most likely a Maya city overgrown by the passage of time. When these cities prospered, sacbeob, the plural form of sacbé or “white roads,” connected various sections of the municipality. Constructed of limestone and sometimes elevated, many of these sacred causeways ran for miles through the jungle, even linking cities. The Cobá-Yaxuná Sacbé is the longest discovered to date, stretching about 62 miles east to west across the Yucatán Peninsula. Imagine constructing nearly straight paths through thick, towering vegetation with no compass or other surveyor equipment. And unlike the Romans who used their cobbled roads for horses and carts, the Maya did not have beasts of burden or pull wheeled conveyances; and they cleared, built, and moved materials only by foot.

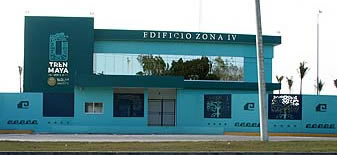

A raised sacbé in the ancient Maya city of Cobá shows a thousand years of growth piercing the once-plastered causeway. Tren Maya tracks seen from Highway 188 near the Edzná Train Station engrave a white swathe across today’s countryside. But now the Yucatán is getting a modern White Road in the form of the Tren Maya, or Maya Train, encircling the entire Peninsula and connecting passengers to areas previously hard to access. The long list of colonial cities and seaside resorts, archaeological sites and expanses of nature reserves, quiet coastlines and offshore treasures include not only the Yucatán Peninsula states of Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo, but also bordering portions of Chiapas and Tabasco.

Izamál is one of six Pueblos Magicos along Tren Maya’s route. An archway in the courtyard of the Basilica San Antonio de Padua Retablo, second in size only to the Vatican’s, frames an ancient Maya pyramid dedicated to their solar deity Kinich Kak Mo. The Basilica was built atop a sacred Maya site using stones stripped from its pyramid. The Basilica’s altar panel gleams with gold leaf. The new rail system provides locals with better options for moving around, and the hope that visitors will utilize it to discover more of the amazing possibilities in the region. Generally considered a beach destination with folks heading to Cancun, Playa del Carmen or Tulúm, the Yucatán is also home to six UNESCO World Heritage sites, six Pueblos Magicos (“Magic Towns”), six Biosphere Reserves, five protected natural reserves, and nine National Parks. Even more enticing to folks like me who like to contemplate in the midst of ancient ruins, the train’s route includes 26 archaeological zones including some previously challenging to access and others newly excavated, restored or recently opened to the public.

Construction of the Tren Maya began in June 2020 with the first section opening in late 2023 and the entire system slated for completion this summer. Seven interconnected sections will cover nearly 1,000 miles and include 20 main terminals and 34 secondary stops. Estimated to travel about 99 miles per hour, 22 of the 32 trains will be electric and the remaining powered by diesel engines utilizing ultra-low sulfur. Three classes of service all include comfortable seating with charging outlets, panoramic windows with curtains, restrooms, cafeteria, A/C, Wi-Fi, lighting, short-circuit TV, luggage space, flat floors with room for mobility-challenged and special needs passengers. Xiinbal, which means "walking" in Mayan, is meant for standard short-distance service. Medium and long-distance travel in Janal class (Mayan for “eating”) includes dining cars serving traditional local dishes. For lengthy or overnight journeys, P’atal (“stay”) offers bigger, reclining seats and some sleeping compartments.

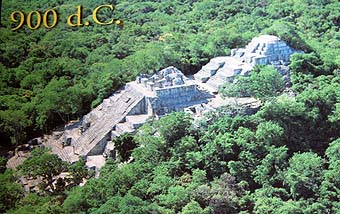

From ground level, the entire second pyramidal complex of Calakmul’s Structure II is obscured from view as it soars 180 feet upward. The entire structure is visible in a poster at Becán. My friend Alfonso calls Tren Maya “the largest construction project in the Yucatán peninsula in nearly 1,500 years!” During Calakmul’s building boom from around 500-830 CE, many of the more than 7,000 structures within this 42-square-mile site were erected or enlarged, including huge ceremonial plazas and residential complexes and some of the tallest pyramids in Mexico. A major seat of power, it rivaled Tikal for dominance and was linked to El Mirador in northern Guatemala by a 24-mile-long sacbé.

Even in today’s modern era, the logistics of the Tren Maya had to be mind boggling. When engineers surveyed potential locations, they decided to use tracks built in the 1930s in Campeche and near Calakmul, but this was just a small portion of the eventual routes. Gravel and limestone pits had to be sourced and dug. More than 720,000 tons of items such as reinforcing steel, concrete and bench material needed procurement. Statistics show a total of 10 contractors, 24 subcontractors, 70 suppliers, and over 350 units of machinery and equipment were brought in.

Alstom, the French company that designed the rolling stock, used Mexico’s iconic railroad construction locale in Ciudad Sahagún, Hidalgo, to build the equipment, estimating it created 4,000 direct and 7,500 indirect jobs. The Mexican government believes 2,100 direct and over 1,400 indirect workers are involved in infrastructure labor. Just planning the housing, feeding and relief stations for all these folks had to keep someone busy.

A new airport has opened at Tulúm to take some of the Riviera Maya visitor load off Cancun. Six new grand hotels are going up within close proximity, even walking distance, of major Maya sites. Locals are opening restaurants and upgrading lodging facilities. Drivers are purchasing new vehicles to shuttle visitors to the attractions, and guides are boning up on history to help explain what visitors are seeing. In addition to boosting tourism, commerce and infrastructure, the Tren Maya promises to protect and promote the archeological legacy along its route.

An important component of the Tren Maya project is PROMEZA, the government Program for the Improvement of Archaeological Zones, which has been working with engineers and contractors to search for, rescue and preserve discoveries made during construction of the train. Thus far, there have been 12 previously unknown archaeological sites; more than 58,000 permanent constructs such as platforms, defensive walls, foundations, residential units and cisterns; nearly 2,000 artifacts including statues and utensils; and nearly 700 human remains as well as funeral chambers with offerings.

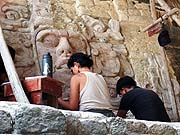

Many sites are being upgraded with new access roads, expanded parking, visitor centers, museums, pathways and signage. Some are undergoing further excavation, consolidation and conservation work. Restoration is underway not only on the structures but also on carvings and murals produced by the ancient Maya. Meticulous and detailed effort is required to clean, adhere fragments, fill gaps, and seal artwork in an attempt to prevent further deterioration.

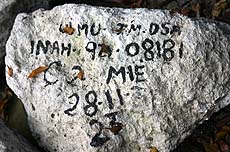

Recent excavations at Chicanná have resulted in thousands of building stones marked with their original location and date of removal, now awaiting reconstruction and consolidation of the original structures. A surveyor at Dzibanché takes measurements of Structure 6.

I meet Lourdes Navarrete working with a team restoring the iconic stucco carvings of the Maya sun god on the Temple of the Masks at Kohunlich. She’s an example of the opportunities PROMEZA has provided in its goal to improve conservation of archaeological sites. Navarrete and her co-workers of college-degreed professional conservators work under the direction of Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), Mexico’s renowned institution that oversees the country’s cultural heritage. With an interest in art and history stemming back to childhood, Navarrete says, “What sparked my enthusiasm for conservation is the feeling this is the small contribution I can make to this world and to humanity, to help in the preservation of historical and artistic heritage for future generations.” She adds, “I find it exciting to preserve what has been hidden and unknown for many years. I think of archaeological heritage as a surprise box since you never know what will be found, and it is a big challenge to help it reach a stabilization level for its preservation.”

Side by side with like-minded folks who hail from many different areas of Mexico (Navarrete is from Mexico City), these conservators will eventually work at other sites yet to be determined, following their dreams while enhancing the rich history and cultural heritage of their country. For all its hoped-for benefits, Tren Maya has not been without controversy. Originally projected at $7.5 billion in US dollars, it is significantly over budget with the latest government estimating more than $28 billion when completed. After promising to “not fell a single tree,” it later admitted 3.4 million had been removed, but environmentalists claim a much higher number. Was anyone actually counting as they fell?

Scarlet macaws, coatimundis (aka Coatis) and motmots are a few of the critters rarely seen or heard in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve these days. Ocelots, jaguars, pumas, howler and spider monkeys, and hundreds of exotic bird species once roamed this 1.8 million acre preserve. A southern section of the railway was to follow an existing highway but after hotel properties complained about disruption to their businesses, the track was relocated and now runs for nearly 70 miles through the fragile ecosystem of the Maya Forest. This has created a major loss of habitat for wildlife as well as the diversity of plant species.

Despite the diligence of all involved, some archaeological and environmental sites have most likely been endangered or even destroyed. And the fragility of the ground itself, peppered with underground caves and rivers, causes some safety concerns and potential damage to the water aquifer system. It is hoped that installing pilings in some of the caves will keep equipment vibrations from collapsing the roofs, and in many places the track will be elevated above ground. What impact will all these improvements and access to draw more visitors have on the ancient Maya cities themselves? My travel buddy Kiyoko echoed my sentiments when she said, “I’m afraid some of these sites will turn into another Tulúm or Chichén Itza – overrun with tourists who don’t appreciate their significance.” Let’s trust that the PROMEZA and Tren Maya projects will not let that happen, but instead preserve and bring promised prosperity. In the next issue of HighonAdventure we’ll explore some of the many wonders to discover in the Yucatán, and why you might want to include a Tren Maya experience in your future plans. ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|