| |

Maori legends tell of a tohunga (spiritual leader) named Ngatoroirangi, who guided the Te Arawa group’s canoe to the eastern coast of a lush and promising island. An avid explorer, he followed a stream inland, climbing higher and higher until he reached the highest peak of Mt. Tarawera. The cold was so intense he thought it would be his demise, so he prayed to his sisters Te Pupu and Te Hoata, the Goddesses of Fire, for help. From the canoe’s homeland in far-off Hawaiki they came, journeying beneath land and sea. When they paused to rest and came to the surface, they left remnants of the fire they were bringing to save their brother. The volcanic areas known as Waimangu, Whakaari and Whakarewarewa are just a few of the places where they made themselves known.

| |

|

|

| |

Mt. Tarawera tops out at 3,363’ post 1886-eruption |

|

Travelling in canoes from East Polynesia in the 13th century, the first inhabitants of this South Pacific archipelago were guided to land by a massive bank of clouds on the horizon. Referring to their new homeland as Aeteaora, Land of the Long White Cloud, it wasn’t until 1634 when the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman stumbled upon these islands that it was renamed New Zealand. And it took the influx of Europeans in the 1800s before the native population were called “Maori”.

| |

|

|

A symbol ubiquitous throughout New Zealand, Tikis represent the First Man, respected as teacher and often portrayed with webbed feet which some suggest show a link to the ocean. If the Tiki is shown with a split tongue or two tongues, it represents a high priest or someone who speaks in both worlds. A Tiki carved with a club denotes a warrior, without a club symbolizes a guardian, and those with a protruding tongue are displays of defiance. |

|

|

|

Whatever combination of tohunga–inspired navigation and cloud-forming landscape that brought them here, the folks from the Arawa canoe journeyed inland to the Rotorua and Taupo districts, where either the Fire Goddesses from Hawaiki or nature’s geological upheavals left vast areas of bubbling hot springs, gurgling mud pools, and steaming mineral-rich lakes. It was the perfect place to settle, with cooking, bathing and heating sources readily available.

| |

|

|

Opening its doors in 1908, the Rotorua Bath House was designed along the lines of a European spa. Doctors sent their patients halfway across the world to “take the cure” in the mineral-rich thermal springs for complaints including arthritis, lumbago and rheumatism. Bizarre treatments included combining water and electricity in a way that today we are warned to avoid. This beautiful Elizabethan structure now houses the Rotorua Museum of Art & History, including tours of portions of the old Bath House. An extraordinary museum with multi-media displays and a wealth of artifacts, it brings to life the story of the region’s geography, history and people. |

|

Ngatoroirangi’s explorations conferred guardianship of New Zealand’s geothermal region to the Te Arawa people, and they became New Zealand’s first tour guides. By the 1830s, missionaries and the occasional European trader were making their way to the area. The number of visitors exploded after 1870, most coming to soak in the mineral-rich waters for various disorders. Those who ventured beyond the healing centers in Rotorua utilized local Maori as guides and boatmen to reach more remote locations. Travelers returned with amazing tales of the area’s distinctive beauty and wondrous sights.

| |

|

|

| |

An artist’s depiction of the eruption of Mt. Tarawera (Image courtesy of the National Library of New Zealand) |

|

In 1886 the Rotorua region was stunned by the eruption of Mt. Tarawera. The entire length of the mountain ridge was ablaze in a gigantic sheet of fire. The eventual eruption rift covered a ten-mile chain of 21 craters along the mountain top. Ash rose nearly seven miles into the sky and blanketed almost 5,800 square miles, destroying seven small villages and nearly 120 lives.

Once a glistening jewel in the fertile Waimangu Valley, Lake Rotomahana provided sustenance to a variety of birds and plant life until the 1886 eruption blew open a series of craters in the basin which slowly filled with water until reaching its present size—twenty times that of the original lake. Thanks to Mt. Tarawera’s little tantrum, Waimangu Volcanic Valley became the world’s newest geothermal ecosystem.

| |

|

|

| |

This feature, part of a section known as Nga Puia o te Papa (Hot Springs of Mother Earth) is formed by boiling hot springs which create mesmerizing patterns of silica |

|

Today, a self-guided 2.5 mile paved path follows Waimangu Stream along a mostly flat to moderately downward incline towards Lake Rotomahana. The walkway winds beside Frying Pan Lake, created from an eruption in 1917 and covering more than 800 acres, making it the world’s largest hot springs. Its 131-degree Fahrenheit waters create fantastic formations of spectacularly colored mineral deposits, including traces of antimony molybdenum, arsenic and tungsten.

| |

|

|

| |

The Te Ara Mokoroa Terrace (Long Abiding Path of Knowledge) was created by a silica-rich spring which began erupting in 1975 |

|

The variety of geothermal and volcanic systems that can be seen along this trail seem endless and endlessly captivating. An awesome vista above the basin of Waimangu Geyser, the world’s largest known geyser, gives pause. Erupting for four years beginning in 1900, it blasted scalding water and rocks 1,300 feet into the air. Hiking trails and optional paths of varying ability levels lead to panoramic views of the Waimangu Valley and many of its features.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The near vertical walls of the Donne Cliffs in Lake Rotomahana are comprised of blistering hot earth that emit constant steam plumes. The red coloring comes from iron oxide. Varying lake level affects the activity of several geysers in this area. |

|

Black swans are among numerous avian species at home in Lake Rotomahana, a protected wildlife refuge

|

|

Once you reach the Lake, you can hike back up, take a courtesy shuttle back to the top, or hop aboard a boat and tour Lake Rotomahana to observe its own separate geothermal system.

| |

|

|

Whakaari Island is estimated to be between 100,000 and 200,000 years old, although what we see today formed “only” about 16,000 years ago |

|

The town of Whakatane lies thirty miles down the coastline from Maketu, where the Te Arawa canoe put ashore. That same distance from Whakatane, out in the Bay of Plenty, sits Whakaari. Rising 1,053 feet above sea level and just over a mile in diameter, it is New Zealand’s only active marine volcano and one of the most accessible anywhere on the planet. It’s full Maori name, Te Puia o Whakaari means “that which can be made visible”, perhaps because the island seems to vanish on hazy days. Captain Cook renamed it White Island because of the clouds of steam which envelope the island.

| |

Inside Whakaari’s crater, eruptions of lava flows and ash create a moon-like landscape where visitors are dwarfed and almost nothing can survive in its acidic environment |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The Maori came to Whakaari to collect sulfur to use as fertilizer in their gardens, and hunt the abundant mutton birds (sooty shearwaters) around the island. The water in acidic streams is soft and tastes surprisingly sweet. |

|

The most incredible thing about Whakaari is the opportunity to visit the island. Not just cruise into the Bay and circle the island and its ridge mounts in a boat, but to don hard hat and gas mask and step ashore on a two-hour guided walk right into the main crater. It seems very odd that the first thing encountered are the rusting remains of an old sulfur processing plant. The operation first opened in 1885 only to be buried the next year by the eruption of Mt. Tarawera. Owners dug themselves out of the ash and began processing again in 1898. About 1500 tons per year of sulfur ore was extracted, but soon dwindled. Now Whakaari is protected as a privately owned scenic reserve and can only be visited with a designated tour operator.

| |

Lakes of bubbling mud, steaming fumaroles, formations of yellow and white sulfur crystals, and the ever-present rotten-egg stench of sulfur greet visitors to Whakaari |

|

It’s quite an interesting experience to weave your way through the steaming crater of an active volcano situated a two-hour boat ride from land. One eye on the ground to avoid stepping into a mound of bubbling mud or a stream running yellow with sulfur. And mind your step, for if you get too close to an edge, you may be treading on a thin layer of crust with a steaming fumarole below. If you look deeply into its depths you can see actual tongues of fire. The other eye is darting outward, upward, backward and sideways trying to comprehend being inside this crater, dwarfed by the evidence of its power and the diversity of its manifestations.

Whakaari sits at an alert rating of 1 on a scale of 1-5, which means she is always active, always steaming. On-site seismographs, survey pegs, magnetometers and cameras are constantly being monitored by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences. For some inane reason, I couldn’t resist the temptation to climb up to one of the cameras, smile a toothy grin directly into its lens, and wave to the poor bloke on the other end attempting to monitor the “activity” on this steaming, belching piece of real estate.

| |

Homes, schools, churches and meeting houses in Whakarewarewa are built adjacent to and even atop geothermal features. Yep, amenities at your humble abode can include your own personal thermal vent or hot springs. Thermal water is not piped into homes so residents use communal baths and kitchens. I’m not sure if the laundry was drying or being steam cleaned. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Houses border the Rahui, a protected reserve with the greatest number of springs and used daily for cooking and bathing. |

|

A visit to Whakarewarewa Thermal Village reveals how the Maori have learned to live and thrive in such a geologically active region. Descendents of the Tuhourangi Ngati Wahiao people who relocated here after the Mt. Tarawera eruption, live in harmony surrounded by 212-degree thermal springs, hot pools, and other geothermal activity.

| |

The local Maori version of an oven, hangi are wooden boxes placed over thermal vents so hot, they can cook a chicken in 20 minutes. Each hangi is identified with its particular temperature, and placing a rock atop the box indicates that particular hangi is in use (so don’t open the lid to see what they’re cooking – it lowers the temperature and can mess with someone’s dinner plans). Because of the ground temperature, gardens are planted in orderly rows of raised beds. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The 208-degree Fahrenheit mineral waters of Korotiotio (Gurgling Throat) are piped along open channels into Whakarewarewa’s communal baths. Well-established protocol provides separate times for men, for women and for families. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Parekohuru (Vigorous Ripples) is the largest and most spectacular of Whakarewarewa’s hot springs |

|

| |

Te Roto A Tamaheke (Lake of Tamaheke) was named for a chief who lived here in times of yore. Beautiful but deadly, a number of hot springs keep the lake above the boiling point. |

|

Te Whakarewarewa (Where the Gods Breathed Fire) thermal reserve is a valley of great geological significance to the Te Arawa, who have lived here for generations. Over 500 named pools and 65 named geysers are found among the boiling mud, sulfur pools and hot springs believed left behind by Ngatoroirangi’s fire-goddess sisters. Despite these harsh conditions, more than 500 varieties of plants and many species of birds now happily live here.

| |

Largest active geyser in the Southern Hemisphere, Pohutu Geyser as seen from Whakarewarewa Thermal Village (left) and from Te Puia (right) |

|

At Te Puia, neighbor to Whakarewarewa Thermal Village, the legendary Pohutu (Big Splash) geyser erupts as many as 20 times each day, sending scalding plums nearly 100 feet into the air. Amazing during the day, it is even more incredible at night.

| |

|

|

| |

Adjacent to Pohutu Geyser, the mineral-rich water from Prince of Wales Geyser forms massive silica terraces |

|

Site of an ancient unconquered Maori stronghold, Te Puia has become a public cultural center offering the chance to learn about the people who have dwelled here for seven centuries, their culture and their land. Many who work at Te Puia are third- and fourth- and fifth-generation offspring of the original settlers, with a wealth of knowledge and stories to pass on.

| |

|

|

The New Zealand Maori Arts and Crafts Institute granted Te Puia the role of guardian of Maori arts, crafts and culture. Home to the national schools of carving (wood, jade/greenstone, stone and bone) and weaving. You can watch these artisans at work and purchase their craftwork. |

|

Te Puia’s evening cultural experience, Te Po, is a wonderful sampling of Maori culture, performance and cuisine. It starts with a group of us approaching the marae (sacred grounds), where we find ourselves confronted by a grimacing warrior, eyes bulging and tongue darting in and out in a ferocious and disquieting manner. Punctuating these startling actions with angry shouts and lunges with a long and serious-appearing spear, we were challenged as to our purpose. Determined to be of peaceful intent, we are allowed to pass.

| |

|

|

| |

Maraes are central to Maori society, and the one at Te Puia is named Rotowhio. Focus of the marae is the wharenui, where all important functions take place. |

|

Proceeding towards the wharenui (meeting house), the powhiri, or welcoming ceremony, continues with a formal greeting of song and music, and we are invited to enter the wharenui. Each part of these exquisite structures holds great significance, recording the tribe’s history through rich and intricate carvings and woven panels. Central to Maori society, they are a traditional gathering place for meetings, celebrations, hosting visitors, and mourning.

| |

The titi torea or stick game was a favorite of all ages, testing agility and coordination. Accompanied by song, four people toss a total of eight sticks, and as they fly from all four directions the receiver must catch and toss them while keeping to the rhythm of the music. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Performances at Te Po include weaponry displays and the blustery posturing of the haka or war challenge, whose aggressive actions were intended to intimidate an approaching enemy. In the safety and hospitality of the wharenui, it is as innocuous and captivating as the intricate poi ball-twirling |

|

It is a night of waiata-a-ringa, songs accompanied by dance and hand and body actions to portray traditional stories and legends. It is an evening to host us, entertain us, and hopefully teach us a bit about the Maori. Afterward, we make our way to the dining area and a bountiful buffet of indigenous and delicious Maori food. (Note: What the Maori call “tuna” is not the beret-wearing, bespectacled Charley we know and love. Think long and black and slippery, as in freshwater eel…)

| |

The Wai Ora Lakeside Spa Resort and its pool overlook Lake Rotorua and Mokoia Island, sacred to the Te Arawa people (images courtesy of Wai Ora Lakeside Spa Resort) |

|

In stark contrast to bathing in sulfurous hot springs or immersing in a tub of electrically-charged water, today’s visitors to Rotorua can pamper themselves at the Wai Ora Lakeside Spa Resort. Situated on the shores of Lake Rotorua, the award winning spa offers a broad menu of options incorporating traditional Maori treatments, and the Mokoia Restaurant features fresh Pacific Rim cuisine served in hearty portions. This 5-star property offers the amenities of a full-sized resort, but with 30 rooms spread along a small grouping of 2-story buildings, the feel is personal and cozy. Absolutely the perfect place to cure the day’s aches from geothermal exploration.

| |

|

|

|

|

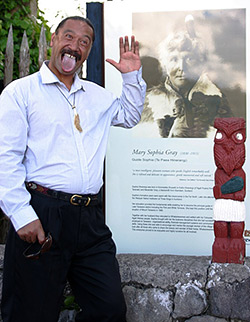

| |

Continuing a tradition dating to the early 1800s, the Maori continue to enthusiastically guide and teach about the amazing land they call Aeteaora. Paora Tapsell at Whakarewarewa Thermal Village follows in the footsteps of his great-great-(I-lost-count-how-many-greats)-grandmother, Mary Sophia Gray, a celebrated Rotorua guide and mentor to many female guides. Mereana Ngatai, descended from a long Te Arawa lineage, teaches art and guides visitors at Te Puia. |

|

Today the Maori comprise more than a third of Rotorua’s population, making the most of a region they still hold in reverence, anxious and willing to share first-hand knowledge that spans many generations. Such extensive geothermal phenomena is seldom as accessible or well-guided as in Rotorua. Nor do many cultures provide the chance to learn, honestly and accurately, about their society. Today’s visitor has the unique opportunity to understand how the Maori learned to live with and flourish in a hotbed of activity atop the Pacific Ocean’s Ring of Fire.

411

http://www.Waimangu.co.nz/waimangu-volcanic-valley

http://www.WhiteIsland.co.nz

http://www.TePuia.com

http://www.Whakarewarewa.com

http://www.RotoruaMuseum.co.nz

http://www.WaiOraResort.co.nz |

|