|

|

PANAMA - OCEAN TO OCEAN IN ONLY EIGHT HOURS |

|||

Story and photos by Brad Hathaway and as attributed |

This is the MV Viking Sky, a 750 foot-long cruise ship that carried us and some 900 fellow passengers from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in just over eight hours. The voyage gave me a chance to learn about the unique seaway that handles more than a third of all the international container shipping to and from the United States.

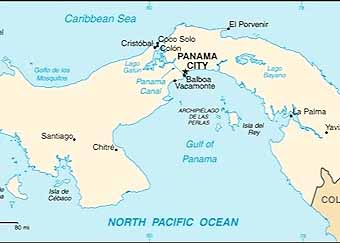

After gold was discovered in Sutter’s Mill in California, setting off the gold rush in the nineteenth century, the fact that the Pacific Ocean is less than 50 miles from the Atlantic Ocean at the Isthmus of Panama has continued to draw both dreamers and doers. After all, if you have to go all the way around the southern end of South America to get from ocean to ocean, it adds about eight thousand miles to a trip from the east coast of the United States to the west. Even at the speed of modern ocean-going ships (about 20 miles per hour) that would take over sixteen days and consume the equivalent of over 800,000 gallons of fuel!

When the Gold Rush of 1849 first got underway, some intrepid souls on the eastern side of the continent booked passage on the then-new steamer ships headed south from New York, stoping in Charlotte, North Carolina and New Orleans, and ending at the mouth of the Chagres River on the north coast of the Isthmus of Panama.There they would hire dugout boats about 20 feet long and 5 or 6 feet wide and local men to pole them up the river as far as it was passable. Then they’d hire a donkey for the ride over the continental divide and down to the southern shore where they would board another steamer to carry them to San Francisco. The first effort to join the oceans by canal was undertaken by the French. They were flush with confidence after creating the Suez Canal which opened just 20 years after the California gold rush. Having joined the Mediterranean with the Red Sea — a distance of 120 miles — the thought of a canal of a mere 50 miles seemed something like a snap. Ah, but there was no mountain between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. The Suez Canal was essentially a one-level “ditch.” A ditch didn’t require the use of locks to lift ships up and then lower them back to sea level on the other side. With Panama’s mountain range — which runs down its “spine” — standing in the way, the French, led by Suez Canal’s conqueror Ferdinand de Lesseps, spent eight years and about a quarter of a billion dollars trying to build the canal before going completely bankrupt. A quarter of a billon dollars in the 1880s was — to paraphrase Everett McKinley Dirksen — a lot of money! After the collapse of the French effort to build a canal, the United States got involved. President Theodore Roosevelt backed the effort which eventually saw the Columbian department of Panama breaking away from its parent country in a revolution backed by U.S. investors (and the United States Navy and Marine Corps). The U.S. granted recognition to this new country three days later and its government granted the U.S. the right to develop a canal. The U.S. then bought the assets of the French effort for some forty million dollars and spent the next dozen years bringing more modern technology to bear to build the largest-to-date infrastructure project in the history of the world. Our passage was to be north to south — from the Atlantic side to the Pacific. As we approached, we settled into “The Explorers Lounge” to watch in comfort. But, of course, we’d step out from time to time for a closer look, or even find a table on deck to watch the passing scene.

Settling in to watch the show

The mouth of the Chagres river, where the intrepid forty-niners began their trek across the isthmus, is just five miles from today’s entrance to the Panama Canal’s channel which leads to the Gatun Locks, the first lock to lift ships for their passage.

The Gatun locks are actually two sets of three chambers. Each chamber lifts or lowers ships about 28 feet for a total lift of 85 feet. A lift is accomplished by filling a chamber with over 25,000,000 gallons from the lake at the top of the locks.

That water is then released into the channel below (and eventually out to sea) when the chamber lowers ships coming from the other direction. Thus, when you count all the locks involved in raising and then lowering a ship, the total amount of water lost from the lake into both oceans for one transit is close to 50 million gallons. It was the tremendous rains of Panama’s rainy season that made the entire system possible. Unfortunately, drought conditions in recent years have caused setbacks in the supply resulting in the necessity to reduce the number of transits in some seasons. But rains this season have been plentiful and the lake behind the Gatun dam is at peak capacity. The size of the individual chambers is astounding. In an effort to make the size understandable in publications at the time the canal was built, an illustration was prepared showing that a six story building would fit inside a chamber and that a locomotive could fit inside the culvert that carries lake water to the chamber.

Three chambers of the Gatun Locks

More modern, larger locks were opened in 2016 with water-conservation features that actually reduce the amount of water released to the sea while lifting and lowering even bigger ships. The MV Viking Sky used the smaller, older locks for its transit. Ships are towed into and out of each chamber by electric locomotives called “mules” which also control their side-to-side motion so they don’t hit the lock’s walls or any other ships sharing a passage through the locks. Amazingly, these mules manage to control huge ships weighing hundreds of thousands of tons with their less than 300 horsepower.

As we exit the upper chamber of the Gatun Locks we find ourselves in Gatun Lake where we are in for a gentle, almost tranquil, cruise of 21 miles. On our right we can just see the top of the Gatun Dam because the water level of the lake is so high. From here it just looks like a bridge with a few legs supporting the roadway above the water level. But in reality, it is the top of a concentric dam that was the largest earthen dam in the world when it was completed in 1913. Today, it impounds as much as four million acre feet of water from the rains in the mountains. That is over a trillion gallons. The water supports the operations of the locks while the dam’s hydroelectric plant generates the electricity that operates the locks. From this view it is difficult to imagine that the dam is over 100 feet above the Chagres river bed below it.

As we cruise across Gatun Lake it is hard to imagine that this huge body of water exists because of man-made dams at both ends and the ships are here because they are lifted 85 feet above sea-level for the transit and then lowered back down again. The Chagres River, once the only way to transit about half the distance, now enters the lake gently under both highway and railroad bridges.

Next we transit the continental divide through the Culebra Cut - the feature that caused the French the greatest challenge and that required the Americans to apply newer technology including the utilization of just-developed explosives, track-shifting capacity on the railroad they built to carry the material away, bigger and better dredges, and huge steam shovels. In 1910 one shovel set a record by taking out in just eight hours over four thousand cubic yards of soil which would have weighed about ten million pounds. During construction, there were 26 landslides that saw some 75 acres of hillside — or, more accurately, mountainside — slide back down into the areas that had already been excavated, requiring not only digging all over again, but widening the area of the trench that became known as the Culebra Cut. Culebra is the Spanish word for “snake;” the cut was dug to make a water passage through the narrow, winding canyon that wound like a snake through the higher mountains on each side. The cut was originally planned to be 670 feet wide at the top, gently sloping down to a 300 foot width at the water level. It turned out that the structure of the mountains they had to dig through was such that it required a cut 1,800 feet wide at the top to be stable for a 300 foot area at the water level. Today, as we pass by the cut, it is hard to conceive of the work done here.

Once we passed through the cut, we approached the single chamber Pedro Miguel Locks which lowers our ship about 30 feet from the level of Gatun Lake to an intermediary lake named Miraflores, which leads us to the Miraflores Locks. There, two chambers will lower us the rest of the way to sea level on the Pacific side of the isthmus.

As we pulled into the Miraflores Locks we saw an impressive viewing platform which is part of the Miraflores Visitor Center where tourists from Panama City come to watch the operation of the locks. From the crowded condition of the platform it does appear that this is a popular spot. Indeed, in 2019, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, it saw a record 9,200 visitors in one day. The crowds are apparently now beginning to come back.

As we transited the final two chambers we watched as water gushed from the lower chamber into the channel that led to the Pacific Ocean. Water use is an important issue in the age of climate change. Indeed, in the drought years of 2016, 2019 and 2023, the canal couldn’t operate at peak efficiency or meet the capacity requirements of international shipping.

The Miraflores Locks

Once clear of the locks, we proceeded toward the Pacific with a last look back at the Bridge of the Americas which carries the Trans-American Highway. You can drive that highway (over a wide range of conditions) from Alaska all the way down to Patagonia in Chile — with the exception of Columbia’s Darién Gap where you have to take a sea-route to skirt the jungle.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|