Seems

impossible that tens of thousands of structures could lie hidden within an

800-square-mile piece of real estate for more than a millennia, so imagine the astonishment in the archaeological community when LiDAR

(“Light Detection And Ranging”) technology made that actually happen. Millions

of laser pulses shoot from the air and bounce off hard surfaces on the ground

to produce a three-dimensional view without vegetation concealing man-made

features. This technology has revolutionized the world of archeology.

The El Petén covers

13,843 square miles, most of it blanketed beneath a thick jungle canopy.

Before

2018, about 100 ancient Maya sites had been identified in this region,

most

still obscured by dense rainforest.

In

2018 a LiDAR project was initiated by PACUNAM, a Guatemalan nonprofit that fosters

scientific research, sustainable development and cultural heritage preservation.

Selecting portions of the Petén region of northern Guatemala, southern Mexico

and western Belize – known location for hundreds of ancient Maya cities

– the 3D laser map stripped away the canopy to reveal more than 60,000 previously

unknown buildings, walls, ceremonial caves and road systems.

The Pyramid of Kukulkán

is recognizable world-wide as the symbol of Chichén Itzá

and the Maya’s prowess

with celestial alignments, yet few realize only a small

portion

of the

buildings at this Unesco World Heritage Site have been explored

and hundreds

more await excavation.

Less

than 150 years ago the Maya civilization was a total mystery. Heck, 200 years

ago the very possibility of such a culture to have arisen in the Americas, let

alone flourished, was considered impossible. When evidence of their achievements came to light, no one believed an

indigenous culture could have developed such wisdom without outside influence.

Areas of particular note include astronomy (knowledge of the Milky Way’s Black

Hole, procession of the equinoxes, cycle of Venus, solar and lunar eclipse predictions),

architecture (the corbel arch, many times more pyramids than the Egyptians), mathematics

(possibly the first in the world to conceive of the concept of “zero”), calendar

(theirs was as accurate as our modern version), and language (one of only five

civilizations in the world to develop a written language).

Even

30+ years ago, refer to the “Maya” and most folks were clueless, at least until

the “Maya Doomsday Prophecy” of Dec. 21, 2012 took the world by storm. Many

recent television specials and series have aired about them but when did the

discovery of marvelous civilization actually begin?

THE EARLY

EXPLORERS

Among the first and arguably the most prolific of early Central

American explorers were John Lloyd Stevens, a lawyer, diplomat, explorer and

writer from America, and Frederick Catherwood, an architect and artist from

England. Hearing rumors of an ancient civilization in the Americas, Stevens and

Catherwood spent 1839 and 1840 uncovering, surveying and recording nearly four dozen sites across today’s Honduras, Guatemala and

Yucatán Peninsula. Catherwood’s use of a camera Lucida to assist in his drawings

produced wonderful images of intricately carved stela (freestanding monolithic

stone monuments) and beautifully decorated buildings.

Three of Frederick Catherwood’s renderings compared to what can be seen today:

Copán’s elaborately-carved Stela A, the ornate 50-foot-tall Nunnery at Chichén

Itzá, and Sayil’s massive 90-bedroom Grand Palace.

(Catherwood’s images from “The Lost Cities of the Mayas: The life, art

and discoveries of Frederick Catherwood”)

Stevens

published two books about their discoveries including more than 200 of

Catherwood’s drawings: 1841’s Incidents

of Travel in Central America, which sold more than 20,000 copies in the

first three months, and 1843’s Incidents

of Travel in the Yucatán. Catherwood’s own 1844

publication, Views of Ancient Monuments

in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán, featured hand-colored panels. The

world was stunned, and puzzled.

In

the latter 19th and early 20th centuries, trained

archaeologists, engineers and architects including American Sylvanus Morley,

German Teobert Maler, and Englishman Alfred Maudslay spent years furthering the

discovery, excavation and recording of ancient Maya sites across the region.

Sadly,

their methods were not always the best even under the “guidance” of

institutions that should have known better. Carnegie Institute-sponsored

archaeologists used dynamite in attempts to locate tombs at Uaxactún, also a

tool of choice for late 19th/early 20th century

excavations at Xunantunich. Part of the façade on Chichén Itzá’s Nunnery was

blasted away by a 19th century explorer. Kerosene was used to clean

the murals at Bonampak.

Palenque’s massive

Palace complex was the victim of horrific carnage during Del Rio’s search

for

valuables and souvenirs. Among other damage and theft, he chopped off a head

and leg

from figures on a stucco pier lining the façade of the Palace.

A

century earlier, in 1786, the Palace at Palenque was the focus of unbelievable

damage when Captain Antonia Del Rio searched for treasure. He hired 79 local

Maya, equipped them with axes and billhooks, set fire to this enormous complex

to allow easier access, then hacked away pieces to send back to his monarch in Spain

as proof of the ancient city they had plundered. To quote from Del Río’s

report, "Ultimately there remained neither a window nor a doorway blocked

up; a partition that was not thrown down, nor a room, corridor, court, tower,

nor subterranean passage in which excavations were not effected from two to

three yards in depth, for such was the object of my mission."

To

add further insult, his report was lost in the Spanish archives. Just a year

prior another group had made the first real examination of the site and sent

their findings to Antigua, Guatemala, seat of Spanish colonial government in

Central America. Where it was lost in the Royal Archives for a hundred years.

During his 1831-32 visit to Palenque, Count Frederick Waldeck set up residence

in the temple atop this pyramid, resulting in its moniker

“Temple of the Count.”

One of the first

Westerners to document the site, he didn’t do any damage

but his sketches incorporated

a lot of imagination, to put it politely.

Teobert Maler hung his Mi Casa sign in Structure 5D-65 of

Tikal’s Central Acropolis,

an immense complex stretching nearly 700 feet long

across four acres.

Maler’s abode during his 1895 and 1904 visits dominates

Court 2

and is commonly referred to as “Maler’s Palace”.

Imagine

actually living inside one of these 1,000-plus-year-old structures while

spending the day excavating a long-lost city.

GETTING THERE IS HALF THE

ADVENTURE

Early

visitors had to go by horseback, trek for days over and through unforgiving

terrain, or take on wild rivers. Today’s choices are

much less challenging but can still be an adventure in itself, even on what

seems should be an easy drive on established routes.

Perched atop a plateau

surrounded by deep ravines in the Motagua River Valley of Guatemala,

the road

to Mixco Viejo twists and snakes it way up the high ridge,

and feels like the

tail end

of a cattle call on the way to Ceibal in Guatemala’s Petén region.

“Sure, we can fit!”

Venturing into the less-traveled regions of the Petén, our drivers knew the

route to Naranjo but the prolific jungle vegetation made clearance and choice

of path sometimes questionable. Taking a different route upon our departure

proved equally challenging, expending about an hour and one tow chain.

Or it can be as simple

as driving onto the hand-cranked ferry across the Mopan River

to reach

Xunantunich, near the Belize-Guatemala border.

Built on a limestone ridge

above

the river, the site enjoys a panoramic view of the upper Belize River Valley

and across a huge swath of Guatemala.

So

if you have to cross a river, why not just start with a boat? Zipping up foliage-festooned

waterways and spotting wildlife is a huge perk. Other than the hum of an

outboard motor, you might think you were joining some early voyager checking

out rumors of long-lost cities in the rainforest.

Normally the boat is in

the water and ready to go, but in the case of Piedras Negras you transport your

watercraft to the launch site on the Usumacinta River and schlep boat and motor

to the water,

hopefully with some able-bodied assistance.

You

might pull up to a dock and saunter into the site, or there may be some stairs

to ascend. Or you may be confronted with an uphill climb that never seems to

end…do not forget your trekking staff.

Ceibal is accessible via

two routes – a sometimes cattle-clogged road (see above) or up the Río la Pasión.

The only drawback to the river

route is a rocky hike into the site beneath the towering ceiba trees

which gave the site its name. And then there’s

Aguateca and the 200 very steep steps up the

300-foot-tall ridge from its landing

site on the Río la Pasión.

Ascent from the landing

spot on the Usumacinta River to the site of Piedras Negras entails an hour’s

uphill hike into one of the most remote parts of Guatemala. As if to tease, near

the top is an abandoned Fordson tractor left by the University of Pennsylvania 1930's

expedition.

Even once you reach a

site, exploring some of the structures may take a bit of huffing-and-puffing. Naranjo’s

Central Acropolis, cleared enough to ascend, still awaits

excavation. The 138-foot climb up Cobá’s

Nohoch Mul pyramid, with a wire cable

assist, rewards with a panorama of the surrounding jungle

punctuated by three

small lakes.

| |

|

|

|

|

A whirly-bird is the

easiest way to access El Mirador, which is about an hour’s flight north of

Flores in the Petén, versus a two-day journey on horseback. Easiest way to see

the five main but sprawling (about a 5-mile walk) groups of structures at Cobá is

by bicycle or pedi-cab, both available for rent at the entrance, with easy

pedaling along the raised roadways criss-crossing Cobá. Often 10-15 feet wide

and elevated a couple of feet, these sacbé (pl. sacbeob) connected ancient Maya cities and some are so massive they have been

seen from space. Cobá itself is the hub of a nearly 100-mile network, one road

plunging in a nearly straight line for 62 miles through the Yucatán forest to a

city near Chichén Itzá.

Here is a much easier way to get to some of Mexico's historic sites, via a two-week tour that includes cities and beaches with Bookmundi's Mexico Unplugged.

WHAT’S THERE

TO SEE?

Pyramids

are often associated with tombs and it’s no different with the Maya, although

not all pyramids contained tombs nor were all tombs placed inside pyramids or

temples.

It is estimated that

70% of Tikal’s temples were burial monuments.

The North Acropolis is a

collection of nearly 100 buildings

sprawling across a 2.5

acre base. Built over many earlier versions,

one includes eight funerary

temples constructed a millennia-and-a-half ago.

Caracol’s 140-foot

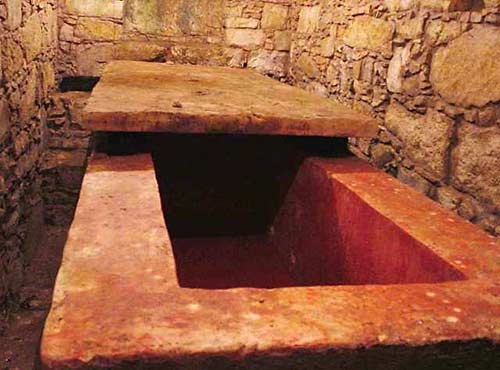

Caana, tallest building in Belize, has three respectably-sized pyramids adorning its summit but not visible from ground level. The tallest of

these held the ornate burial of a woman, and remnants of red paint on the back

wall above her tomb can still be seen (above

left). The large pyramidal Structure 42 at Tenám Puente included several

burials, some in niches built of rubble (above

right), others in circular graves,

and those whose cremated remains were

placed in clay pots.

The Temple of the Red

Queen contained the second-richest burial at Palenque, exceeded only by Pakal,

even though early looters removed much of the offerings. Everything inside the

tomb was covered

in a heavy layer of cinnabar (mercury sulfide), which to the

Maya represented death and rebirth.

Some tombs are so modest

they were overlooked for decades. In 2012 at Takalik Abaj,

excavation of a

16-foot tall grassy platform such as this one (Structure 11)

revealed the

2,500-year-old tomb of the Vulture Lord beneath

an eight-foot mound of clay and

cobblestones.

Piedras Negras burials include

the affluent tomb of the third ruler who died in 729 CE, as well as Tatiana

Proskouriakoff who is credited with “cracking the Maya code” and deciphering

the intricacies of Maya politics. Although she died in 1985, her ashes couldn’t

be interred in the West Acropolis until 1998 when Marxist guerrillas using the

area during Guatemala’s civil war cleared out.

Ancient

Maya cities were a stunning site with their white-plastered plazas surrounded

by brightly painted buildings, many of which still carry traces of reds, blues

and other hues. Murals, painted walls and carved friezes still convey the artistic

skill of these skilled artisans.

Near the doorway of

Structure II at Chicanná, red glyphs painted on an earlier layer

were revealed

when an over-layer of stucco fell off (above

left).

Huge sculptures of kings and gods adorned the walls of Cancuén’s

Palace (above right).

Colorful doorways and

walls are still evident on the Temple of the Bats

and Structure 25 “Las Manitas”

in San Gervasio on the island of Cozumel.

Murals are found across

the Maya region including Yaxchilán’s Structure 33 (above left)

and Mayapán’s Room of the Frescos (above right).

Earlier, more elaborate

and history-breaking examples

are being discovered all the time.

Applying a thick layer

of stucco, the Maya carved facades and friezes of their gods and mythology.

Structure XIII at Becán contains a massive façade (above left) protected by a pane of glass.

At nearby Balamkú, an

earlier construction under Structure I, “House of the Four Kings,” was

decorated

with a 55-foot-long, nearly 6-foot-tall frieze of the Maya cosmology, traces of original paint are still evident.

The significance of red

handprints isn’t certain, perhaps a reference to the Maya god Itzamná who was

also called Kabul, “divine or

celestial hand.” Examples are found in the Temple of the Frescos at Tulúm (above left), the main corbel vaulted

entry to the Nunnery at the Unesco World Heritage Site of Uxmal (center), and in Structure 25, “ Little

Hands” (named for the handprints) at San Gervasio.

There

isn’t much opportunity for regular folks of ordinary means and physical ability

to experience an Indiana-Jones-type adventure, but visiting ancient Maya cities

comes pretty darn close. While amazing, colossal structures can overshadow details

like tombs, murals and larger-than-life-size carved façades, there is a mystery

to walking the paths, climbing the stairs, and peering into rooms inhabited a

thousand or more years ago.

This

journey of discovery isn’t over - in next issue’s Part 2 we’ll look at some

current excavation projects, some major discoveries, and the havoc wrought by

looters and, sadly, the Catholic Church.

Other

Maya-related articles by Vicki Hoefling Andersen:

Belize: The

Western Frontier

Belize: The

Eastern Edge

Lords of the Petén, Guatemala

Life Along the

Rio La Pasión

Highlands of Guatemala

Palenque, Mexico

Chiapas, Mexico

Abandoned

Cities of Chiapas, Mexico

Ancient Cities

of the Rio Bec

Ancient Cities of the Río Bec

Part 2

Roaming

Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula

Isla Mujeres:

Island of Women

The Maya &

2012: A New Beginning

|